Your Requirements Suck

But crappy requirements probably aren’t the problem.

Hey y’all –

Before I jump right into insulting your requirements, I’d like to share some recent events at Nerd/Noir.

—

On October 16th, 12-1p EST, I’m co-hosting a webinar with Anne Steiner called From Technical Debt to Technical Investment. You can sign up here.

We’ll explore the semi-wicked problem of “tech debt” from both engineering’s and product’s perspectives. We’ll also share our playbook (did you know we created a playbook framework that’s free to use, remix, and share?) to help teams balance customer outcomes with system qualities.

And if you can’t make that date/time, go ahead and sign up, and we’ll ensure you get the recording and playbook sent straight to your inbox.

—

We’ve done a lot of Developer Experience consulting over the last few years. Our partnership with DX lets us conduct a sweet (95%+ completion rates, dozens of metrics, solid research) snapshot survey that gives everyone—leaders, engineers, product people, and us—transparency into what’s working and what’s not.

Our clients are finding that the data from the DevEx 360 platform is driving productive conversations and, more notably, action around continuous improvement. It’s a quick and cost-effective way to create situational awareness around DevEx. Check out our Developer Experience Insights service right here.

—

This post is extracted from a talk I gave at Travelers’ internal “Enterprise Engineering Day” conference a week ago. Thanks to the good folks at Travelers for having me! If you’d like someone from Nerd/Noir to speak with your group, check out our internal talks page for a list of topic ideas.

On to the article!

/ Dave

P.S. To my fellow business goths out there: HAPPY SPOOKY SEASON! 💀🎃👻

—

Your Requirements Suck

“The requirements aren’t good enough.” You’ve heard it. Perhaps you’ve said it. It’s a common complaint from engineers.

But it doesn’t tell you all that much. It describes a symptom, not the disease. What about the requirements makes them inadequate?

Why Your Requirements Suck

Unclear or ambiguous requirements are single effect with multiple causes. A few of the usual suspects:

Game of telephone - the original intent of a requirement is misshaped through a series of point-to-point conversations.

Unclear - the requirement is ambiguous and open to creative interpretation, perhaps with many unchecked assumptions.

Shifting Sands - requirements change or are swapped due to insufficient discovery or moving target priorities.

But Why Tho - engineers working on a requirement question its purpose or value.

Cold Handoffs - the requirement is pulled from a backlog, and backlogs aren’t great storytellers.

Overconfidence - just because you think it’s a requirement doesn’t mean it solves a problem for a user or customer. See also: overly speculative.

Your requirements might suck because of one of these reasons or because of all of these reasons. Game of telephone frequently conspires with cold handoffs. Shifting sands and Overconfidence and But why tho are the unholy trinity of a poorly understood or empowered product management capability.

Maybe the idea that requirements can ever be good enough needs a bit of rethinking.

System Effects

If we don’t address the causes above, what’s likely to happen? Let’s look at a causal feedback diagram illustrating one likelihood.

In this diagram, we have three values:

Trust is the belief that our customers and stakeholders have in us to solve problems and create value.

Rework is the time we spend changing what we’ve delivered because the first delivery was wrong.

Throughput of Value is the value we deliver to customers or stakeholders in a given period.

The arrows with the little circles with a plus or minus indicate in which direction these values travel:

As the amount of Rework increases, perhaps due to not understanding requirements, our Throughput of Value decreases. We have to spend more time getting things right.

As Throughput of Value decreases, the Trust our customers or stakeholders place in our ability to deliver value also decreases. This is bad.

As Throughput of Value decreases and Rework increases, Trust erodes ever faster.

We have a vicious circle that leads to a classic Western standoff. Customers don’t trust the team’s ability to deliver, and the team doesn’t trust the customer or product manager’s requirements. We already know how the engineers feel.

What’s going wrong here? If it’s really about crappy requirements, shouldn’t we make them better? Just requirements harder!

Questionable Assumptions

Before we start fixing our requirements practice, I have a question: Why do we think written requirements are a good idea in the first place? Let’s go digging for assumptions.

A quick brainstorm reveals several questionable, perhaps faulty, assumptions.

Are requirements even knowable up front? We know this: The highest-quality feedback comes after users have used working software. Unfortunately, engineering is an expensive undertaking. I understand why we might try to de-risk user needs by validating our ideas before starting principal engineering. Though I’m pretty sure requirements-centered activities and artifacts aren’t the answer.

When requirements are unclear, you shouldn’t assign blame to the artifact or its creators. You have to look at the system.

It’s the product manager’s (or product owner’s or BA’s) sole responsibility to write acceptance criteria. If you believe that, you’re likely experiencing the problems of cold handoffs or game of telephone.

User stories are a written medium. You’re probably sick of hearing this (I know I am), but user stories were always meant to be placeholders for conversations. Many companies that adopted agile practices simply slapped the label “user story” on their business requirements docs and moved on with their lives.

Assigning new vocabulary to existing practices, roles, or processes never worked. Business analysts or project managers became product owners in a two-day training, program management offices were replaced by release trains, and the list goes on…

Putting too much weight (or hope) on a handoff-driven requirements process assumes you have a lot of other things in order. When requirements are unclear, you shouldn’t assign blame to the artifact or its creators. You have to look at the system.

Assumptions: Checked

Let’s unravel some of those nasty assumptions.

The idea that requirements are knowable up front is a broad, context-free statement. Many of the products we work on benefit from learning and experimentation. If this is your context, frame what you want to deliver, but don’t get it twisted. You’re not creating requirements; you’re making an educated guess.

Hopefully, that guess will be backed by solid product discovery. In your discovery missions—also hopefully—you’re inviting technical representation to shift left, upriver in the value stream.

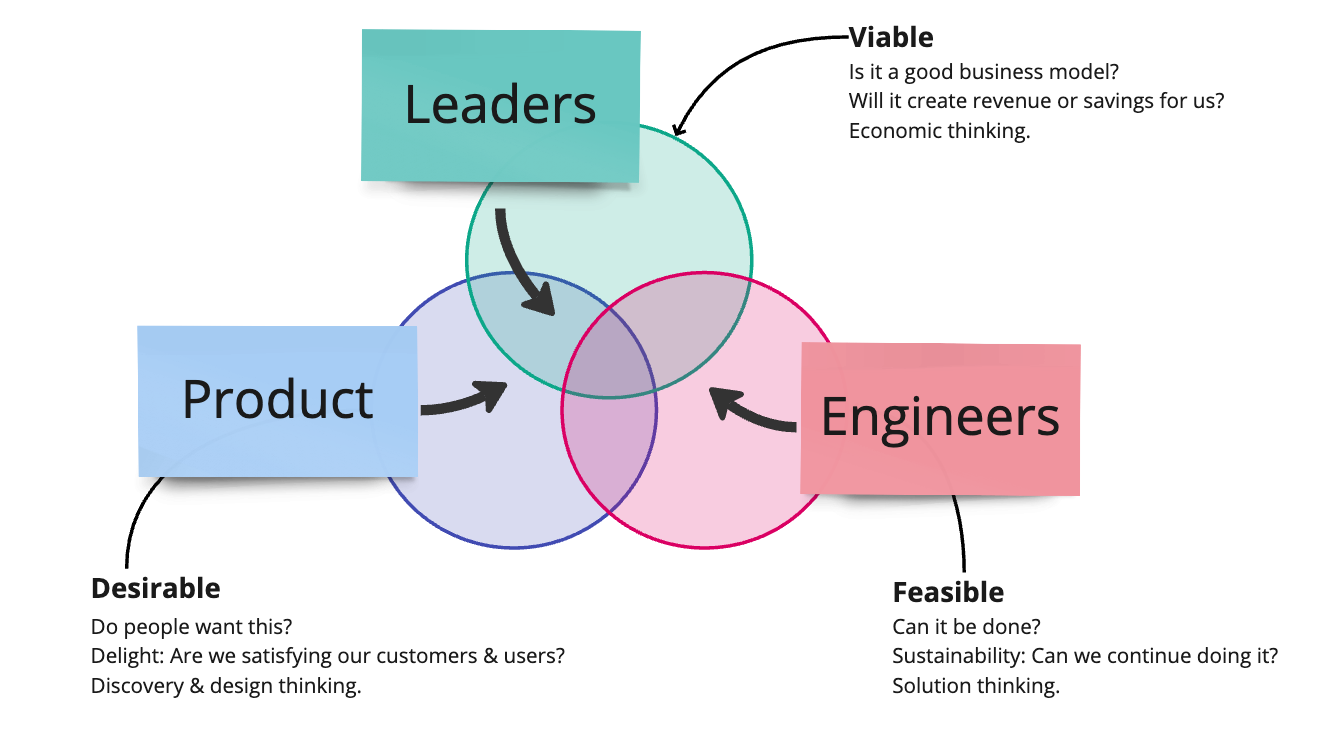

Creating requirements should be a joint activity. It’s not the sole responsibility of the “product person” on your team. A product manager cannot anticipate every edge case, and as the engineering work unfolds, there will be questions, what-abouts, and many small decisions to make. All good reason for inviting engineering along for the ride.

We could pick apart all these faulty assumptions and the underlying problems they hide when unchecked, but what could we do to change the system?

One Small Step

Collaboration is the solution. Unfortunately, it’s not an easy solution.

Real, genuine collaboration is a skill that you must relearn with every new group of people you work with. It requires that:

Product-focused people (PM, UX) continuously engaged throughout delivery, negotiating, and refining requirements.

Engineers take their hands off their keyboards and work with their cross-functional teammates, valuing that time.

Stakeholders provide timely feedback in tight loops to guide what we used to call requirements (what we think) toward specifications (what is).

Notice I didn’t call collaboration a simple solution. It’s not. Effective collaboration means courting conflict and committing to making many small resolutions. Effective collaboration means navigating tricky tensions, such as the desire for delivery speed and solution quality. Effective collaboration means occasionally giving so that you may get down the line.

If you want something done right, do it together.

More than anything, we can’t collaborate if our partners don’t agree to do the same. Real collaboration doesn’t work without us taking at least one small step toward one another.

Engineers: become co-authors of requirements. Ask to ride-a-long on a product discovery mission or design review.

Product people: understand that engineers spend a lot of time thinking about your (y’all’s) product. They might even have something valuable to say about its direction.

Leaders: show up and give the feedback required to shape speculative requirements into actual specifications.

Go ahead, everyone, take one step toward the center.

If you want something done right, do it together.